- Home

- David Liss

The Ethical Assassin Page 2

The Ethical Assassin Read online

Page 2

She was young, but getting old in a hurry. Her face, pretty at least in theory, was splattered with light freckles and punctuated by a pert little nose, but her eyes, the brown of the redneck’s Yoo-hoo, were raked with deep crow’s-feet and underscored by extraordinarily dark rings. Her fine, beach-sand-colored hair was pulled back in a ponytail that could be either youthful or haggard. There was something about her expression- she reminded me of a balloon from which the air was slowly leaking. Not so that you could see it deflate or hear its flatulence, but you’d leave that balloon looking fine and come back in an hour to find it drooping and slack.

I pretended I didn’t notice her misery, and I grinned. The grin hid my hunger, my thirst, my boredom, my fear of the bucktoothed redneck in the Ford pickup, my hopelessness in the absence of visible moochiness, my despair at the thought that Bobby would not come by the Kwick Stop to pick me up for another four hours.

At least I’d already scored that day, getting into a house in my first hour out. I’d made $200 right there, just like that, from those poor assholes. Not poor as in sad-sack, but poor as in ill-fitting clothes, broken furniture, leaking kitchen faucet, and a refrigerator empty but for Wonder bread, off-brand bologna, Miracle Whip, and Coke. Let me be absolutely clear about this. Not once, not one single time, no matter how happy I was to make a sale, did I ever do it without the acid tinge of regret. I felt evil and predatory, and often enough I had to bite back the urge to walk out halfway through the pitch, because I knew the prospects couldn’t afford the monthly payments. They would pass the credit app, I was almost sure of it, but when it came to paying the bills, they’d have to trade in the Coke for generic cola.

So why did I keep doing it? In part because I needed the money, but there was something else, something bigger and more seductive than money, drawing me in. I was good at sales, good at it in a way I’d never been good at anything in my life. Sure, I’d done well in school, on my SATs, that sort of thing. But those were solitary activities, this was public, communal, social. I, Lem Altick, was getting the best of others in a social situation, and let me tell you, that was new, and it was delicious. I would look at the prospects slouching into their sofa, people who’d never done anything to hurt me, and I had them. I had them, and they didn’t even know it. They’d hand over the check and shake my hand. They’d invite me back, ask me to stay for dinner, ask me to meet their parents. Half the people I tricked into buying told me if I ever needed anything, if I ever needed a place to stay, I shouldn’t hesitate. They lapped up everything I served, and, evil or not, it felt good. It made me ashamed, but it still felt good.

Now I wanted another one. The company offered a $200 bonus for a double, and I wanted to rack up another score before I saw Bobby again. Of course I wanted the money; $600 for the day would be pretty satisfying. And I’d done it before, my very first day on the job, in fact- an act that had all but anointed me the new boy wonder. The truth was, I loved the look on Bobby’s face- the happy surprise, the sheer giddiness of his expression. I couldn’t have said why Bobby’s approval was so important; it even troubled me that I cared so much. But I did care.

“Hi there. I’m Lem Altick,” I told the gaunt, sort-of-pretty-sort-of-bitter woman, “and I’m in your neighborhood today talking to parents, trying to get some feedback on how they feel about the local schools and the quality of education. Do you by any chance have children, ma’am?”

She blinked at me a couple of times- appraising sorts of blinks. The lizards were blinking, too, but more slowly, and their eyelids came up from the bottom. “Yeah,” she said after a moment to think. Her gaze went right past mine and toward the blue pickup, which was still parked alongside the road. “I got kids. But they ain’t here.”

“And may I ask how old they are?”

She blinked again, this time more suspiciously. It had been only a couple of years since a boy named Adam Walsh had disappeared from a mall in Hollywood, Florida. His head had been found a couple of weeks later a few hundred miles to the north. Nobody had ever again looked the same way at kids or at strangers who showed an interest in kids.

“Seven and ten.” Her hand gripped the side of the door more tightly, and her fingers went white around her chipped fuchsia-polished nails. She was still looking at the Ford.

“Those are great ages, aren’t they?” Not that I knew. I’d never spent much time around kids since being one myself, and in my experience, those ages were as unredeemably rotten as the rest. Still, parents liked to hear that sort of thing, or at least I figured they did. “So, if your husband is home, I was hoping I might be able to take just a few minutes to ask you some questions for a survey. Then I’ll be out of your hair. You’d like to answer a few questions about your ideas on education, wouldn’t you?”

“You with him?” she asked, gesturing toward the pickup with a flick of her first two fingers.

I shook my head. “No, ma’am. I am here in your neighborhood to talk to parents about education.”

“What are you selling?”

“Not a thing,” I told her. I feigned a slight, almost imperceptible surprise. Me? Ask you to buy something? How very silly. “I’m not a salesman, and if I were, I’d have nothing to sell you. I’m just asking some questions about the local educational system and your level of satisfaction. The people I work for would love to hear what you and your husband have to say. Wouldn’t you like to tell us what you think of the local schools?”

She pondered this for a moment, clearly unfamiliar with the idea that anyone could possibly care what she had to say. I’d seen the look before. “I don’t have the time,” she said.

“But that’s exactly why you should talk to me,” I said, using a technique called “the reverse.” You told the prospect that why they couldn’t do it or why they couldn’t afford it was exactly the reason they could. Then you dug deep and came up with a reason that it was true. “You know, studies show that the more time you dedicate to education, the more free time you have.” I made that up, but I thought it sounded reasonable.

I guess she did, too. She glanced again over to the Ford and then back to me. “Fine.” She pressed open the screen door. The lizards held their ground.

I followed her inside, the fear of the redneck now almost forgotten in the excitement of a looming commission. I had not been doing this long, not compared with Bobby’s five years, but I knew getting inside the house was the hardest part. I might go days without anyone letting me in, but I’d never once made it in without making the sale. Not once. Bobby said that was the sign of a real bookman, and that’s what I was turning out to be. A real bookman.

I stood in the trailer. Me, this desiccated woman, and her still unseen husband. Only one of us was going to walk out of there alive.

Chapter 2

INSIDE, THE SMELL OF OLD CIGARETTES replaced the stench of garbage and filth. Everyone in my family smoked cigarettes, every last relative with the exception of my stepfather, who smoked cigars and pipes. I’d always hated the odor, hated the way it seeped into my clothes, my books, my food. When I was young enough to still bring a lunch to school, my turkey sandwich would smell like Lucky Strikes- my mother’s improbable brand.

The woman, who also smelled of cigarettes and had nicotine stains on her fingers, told me her name was Karen. The husband looked younger than she did, but also like he was aging faster, and I could see his balloon would be out of air before hers. Like Karen, he was unusually thin, with a hollowed-out look to him. He wore a sleeveless Ronnie James Dio shirt that showed bony arms insulated with layers of wiry muscles. Straight reddish hair fell to his shoulders in a southern-fried rock cut. He was good-looking in the same way as Karen, which was to say he might have been more appealing if he didn’t give the impression of someone who hadn’t eaten, slept, or washed in the better part of a week.

He came in from the trailer’s kitchen, holding a bottle of Killian’s Red by its neck as though he were trying to strangle it. “Bastard,” he said. Then he switched

the bottle to his left hand and held out his right for shaking.

I wasn’t sure why he would call me a bastard, so I held back.

“Bastard,” he repeated. “It’s my name. It’s a nickname, really. It ain’t my real name, but it’s my real nickname.”

I shook with what I considered an appropriate amount of skepticism.

“So, where’d you find this guy?” Bastard asked his wife. It came out just a little too fast, a little too loud, to be good-natured. With a tic of the neck, he flung back his longish hair.

“He wants to ask us some questions about the girls.” Karen had wandered into the kitchen, separated from the living room by a short bar. She gestured with her head toward me, or maybe toward the door. The two of them were jerking their heads around as if they were in a Devo video.

Bastard stared. “The girls, huh? You look too young to be a lawyer. Or a cop.”

I attempted a smile to mask the kudzu creep of alarm working over me. “It’s nothing like that. I’m here to talk about education.”

Bastard put his arm around my shoulder. “Education, huh?”

“That’s right.”

The arm came off almost right away, but the inside of the trailer was beginning to feel more dangerous than outside. I’d seen some weird stuff inside people’s homes-Faces of Death videocassettes mixed in with the Mickey Mouse cartoons, a jar of used condoms on a coffee table, even a collection of shrunken heads once- but this weirdly intimate moment put me on my guard. I didn’t leave, though, because the redneck was surely still out there, and that made it a lose-lose deal. Might as well stay where there was a chance of closing a deal.

Not much of a chance, though. I took a guarded look at the trailer; it was the kind of place that warded off salesmen the way garlic warded off vampires. They had no toys scattered around, no empty cases from kids’ videos or coloring books or haphazard Lego towers. They had no toys of any kind. And there wasn’t much in the way of adult crap, either. There were no plastic hanging plants or not-available-in-stores garish cuckoo clocks or oil paintings of clowns.

Instead, they had a beige couch and a phenomenally not matching blue easy chair and a cracked glass coffee table full of beer bottles and beer bottle rings and coffee cup stains. A single coffee mug- white with OLDHAM HEALTH SERVICES printed in bold black letters- rested against the glass in such a way that I felt sure it would take both hands to pry it off. The coffee inside had condensed into tar.

In the kitchen, the linoleum floor, the kind of tan that looked dirty when clean and extra dirty when dirty, was chipped and peeling and in places curling up. In one spot it had rolled up over a white towel and looked like a Yodels.

Yet despite it all, there was some small reason to hope. Yes, their stuff was absolutely awful, and yes, they clearly had no money, except- Except. A chipped Lladró, a ballerina in midtwirl, sat on top of the television. Maybe it had been a gift or inherited from a grandparent or found by the trash. It didn’t matter. It was a Lladró, and Lladrós were gold. Lladrós were moochie. The spirit of mooch, no matter how diminished and repressed, dwelled within.

Bastard now put a hand on my back. “So, you’re like, asking parents questions about their thoughts on education? Something like that?”

Had he heard me at the door? “That’s right. About education and your kids.” The kids who, I noticed, left no hint that they’d ever passed through their own home.

“So, what you selling?” A spark of amusement flashed in his dull eyes.

“I’m just here to ask questions about education. I’m not here to sell.”

“Okay, see you later, jerk-off. There’s the door. Get out.”

I was about to open my mouth, to observe politely that his wife had said she wanted to take the survey, and after all, it would only be a few minutes. But I didn’t get that far. Karen pulled him aside to the bedroom, where they exchanged some heated and hushed words. In a minute or two they came out, and Bastard had a plastic grin on his face.

“Sorry about that,” he told me. “I guess I didn’t realize how much Karen wanted to talk about, you know, education.” He slapped my back. “You want a beer?”

“Just water or soda or something, if you don’t mind.”

“No problem, buddy,” Bastard said with an enthusiasm that frightened me more than the shoulder squeezing.

Karen led me to the kitchen card table, where she directed me to sit with my back to the door in a metal folding chair, the kind they brought out for ad hoc municipal gatherings in school gymnasiums. She made some uneasy small talk and handed me lemonade in another OLDHAM HEALTH SERVICES coffee cup. I still felt a phantom tingling on my shoulder where Bastard had grabbed me, but the anxiety was beginning to dissipate. They were strange- strange and unhappy- but almost certainly harmless.

I tried not to drink the lemonade in a single gulp. “This who you work for?” I asked, gesturing toward the coffee cup. I didn’t direct the question toward either of them in particular.

Bastard shook his head, let out a little noise, something short of a laugh. “Nah. We just have them.”

“They’re nice,” I said. “Nice and thick. Keep the coffee warm.” I waited a moment to let the idiocy of my words dissipate. “What do you folks do?”

“Karen used to waitress some,” Bastard told me, “till her back started to bother her. I’m the site manager for a hog farm.”

Site manager sounded impressive enough, as though they’d be able to make the payments, at least, which was all I needed. I unfastened the strap of my bag, and took out one of the photocopied survey sheets.

I set my papers on the kitchen table next to the basket of plastic fruit- another faint hint of moochiness there- and asked Bastard and Karen the questions. When I’d been in training, I’d balked at first seeing them, sure anyone with a pulse would smell the bullshit a mile off. But Bobby had laughed, assured me that this sales pitch had been designed by experts. It was one of the most successful pitches ever devised. Having sold for three months now, I had no problem believing it.

Would your child benefit from greater access to knowledge? Would you be happier if your child was learning more? Do your children have questions left unanswered by their education? The last one was my personal favorite: Do you believe that people continue to learn even after they complete their schooling?

“They say you learn something new every day,” Bastard announced cheerfully. “Isn’t that right? Hell, just last week I learned I was even stupider than I thought.” He let out a big laugh and then slapped his leg. Then he slapped my leg. Not hard, but even so.

Karen watched Bastard. There was a kind of suspicion there, even a wariness. If I had not known they were married, I might have thought they’d never met before. As it was, I figured they were well on their way to petty claims divorce court. Not the best environment in which to sell, but pickings were, at the moment, slim.

I dutifully wrote down their answers and took a moment to review the responses, to study them. I put on a serious face, knit my brow, contemplated the gravity of their answers.

“All right,” I said. “I just want to be sure I understand you now. So you think that education for children is important?”

“Sure,” Bastard said.

“Karen?” I asked.

“Yeah.” She nodded.

This was all part of the pitch- make them agree as much and as often as possible. Get them in the habit of saying yes, and they’ll forget how to say no.

“And you think that items, products, or services that aid in a child’s education are good ideas? Bastard? Karen?”

They both agreed.

“You know,” I said with an expression of puzzled amazement- I hoped it looked spontaneous, but I’d practiced it in the mirror-“looking over all of this, it seems like you two are just the sort of parents my employers would love to have me talk to. You obviously care a great deal about your children’s education, and you have a deep commitment to seeing that their educational needs ar

e met. My company has sent us out here to try to measure the level of interest for a product they intend to introduce in this area. Now- Karen, Bastard- since you two are obviously such education-oriented parents, it occurs to me that you’re exactly the sort of people I’ve been authorized to show a preview of these products, assuming, of course, you’re interested. Do you think you’d like to look at something that is beautiful, affordable, and, best of all, will significantly increase the education and, ultimately, income potential of your children?”

“Okay,” Bastard said.

Karen said nothing. The lines around her eyes deepened, her cheeks collapsed, and her thin lips parted as she began to speak.

I would not let her. I’d never been asked to leave at this point, but I knew perfectly well that it could happen, that it would happen here if I let it. Outside, the redneck in the pickup might still be waiting, and I didn’t want to find out one way or the other.

“Let me tell you up front,” I said, barely managing to beat her to the punch, “that I’ve got a lot of people I need to see in this area. I’m happy to take the time out to show you this stuff, but first we need to make a contract, the three of us. If at any point you lose interest or you think that it’s not the sort of educational tool you’d like to provide for your children, just let me know. I’ll get up and leave. I don’t want to waste your time, and I’m sure you understand that I don’t want to waste my time, either. So can you promise me that? The minute you don’t want to see any more, you’ll speak up? That’s fair, isn’t it?”

“Fair.” Bastard let out a loud, phlegmy snort. “Congress never passed a law saying life had to be fair. Not unless you’re a Spanish, a black, a woman, or a congressman.”

I smiled politely, doing my best to appear nonjudgmental, another skill I’d honed over the past three months. “C’mon, Bastard. Let’s be serious. It’s fair, isn’t it.”

The Whiskey Rebels

The Whiskey Rebels Renegades

Renegades The Twelfth Enchantment: A Novel

The Twelfth Enchantment: A Novel The Day of Atonement

The Day of Atonement The Devil's Company

The Devil's Company Randoms

Randoms Paleo / The Doomsday Prepper

Paleo / The Doomsday Prepper Rebels

Rebels A Spectacle of Corruption

A Spectacle of Corruption The Twelfth Enchantment

The Twelfth Enchantment The Coffee Trader

The Coffee Trader The Ethical Assassin

The Ethical Assassin The Devil’s Company: A Novel

The Devil’s Company: A Novel The Double Dealer

The Double Dealer The Whiskey Rebel

The Whiskey Rebel A Conspiracy of Paper bw-1

A Conspiracy of Paper bw-1 The Devil's Company bw-3

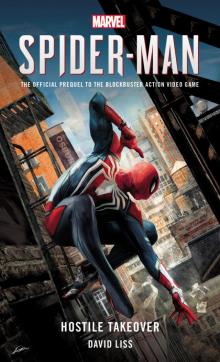

The Devil's Company bw-3 Marvel's SPIDER-MAN

Marvel's SPIDER-MAN