- Home

- David Liss

The Twelfth Enchantment: A Novel Page 21

The Twelfth Enchantment: A Novel Read online

Page 21

“It will. I should not have let you come if I were not prepared for what we might find,” said Mr. Morrison. “I don’t much care for ghosts—bit of a bad history there—and the ones here are more unpleasant than most.”

Lucy laughed nervously. She was eager to move on. “You know the way to the library?”

“He has no great library,” Mr. Morrison said. “But I know where he will have such books as he possesses—in the old drawing room.”

Again, there was that tone in his voice, but Lucy did not ask questions. Instead, she took Sophie’s hand and followed Mr. Morrison into the great expanse of the entryway. Here was a vast, cold stone room with vaulted arches. There was little in the way of decorations or wall hangings, and Lucy perceived it was but an entrance to the abbey proper. Somewhere in the distance she heard a slow drip of water.

Mr. Morrison turned back to her. “This is the crypt.”

“Splendid,” she answered.

They turned right and proceeded up a great and broad stone staircase, the steps wide enough to be negotiated without much difficulty by a horse. Horse droppings scattered about the floor gave evidence that Byron had actually ridden indoors. Lucy also observed overturned plates of food upon which rats nibbled, occasionally turning to stare at them brazenly. There were, however, no ghosts in evidence.

At the top of the staircase they entered the great dining room, which showed more evidence of horses, discarded food, and overturned and shattered bottles of wines. Cobwebs tickled their faces, and they heard the scurry of little animal feet—more rats most likely, but this being Newstead, there could be no assurance that they would not be poisonous lizards or African monkeys or anything else Byron’s imagination might desire and his credit might procure.

Through a carved doorway they entered a corridor which took them to a short set of steps, and then a door, which Mr. Morrison pushed open. They followed him inside.

It was a massive room, sixty feet long, and almost half as wide, and it was the most orderly and well-kept space Lucy had yet seen in Newstead. There were paintings upon the walls, and comfortable furnishings near the ornate fireplace. Along the far wall, even in the dark, Lucy could perceive bookshelves. Relief washed over her. Their journey was near an end.

“This is the great drawing room,” said Mr. Morrison. “Byron keeps his collection here. Nothing like what a gentleman would call a library, but a few hundred volumes, so this may take some time. Let us see if we cannot find some candles or lamps to light to make the work go faster.” He raised up his lantern and then began to let out a long string of uncharacteristic curses.

Lucy saw at once his reason. The shelves along the wall, where Byron’s books ought to have been, were completely empty.

“Damn him,” said Mr. Morrison. “I should have known he would do something of this sort.”

Lucy tugged on his sleeve.

“You will have to endure my language,” he said. “And the deaf girl cannot hear me.”

“Not that,” said Lucy. “By the door.”

Mr. Morrison turned his lantern toward the door. At first, he saw nothing in the gloom—Lucy watched him shift his light about in search of what had alarmed her—and then he saw it, the massive gray wolf, its yellow eyes reflecting the lantern’s glow. Even in that dim light, they could see that its mouth was open, its head low to the ground. The animal let out a low, rumbling snarl.

They stood on the far side of the furnishings, so the sofa and chairs and tables were between their position and the wolf’s, but that would do them little good. Very slowly, Lucy reached into the inner lining of her cloak and removed a small felt pouch. Loosening the drawstring, she began to sprinkle its contents on the floor around them while she muttered an incantation. She hoped it did not need to be spoken clearly, for she was still slightly embarrassed to do such things in front of other people.

“Monkshood,” she told Mr. Morrison when she was done. “The wolf won’t like it.”

“Very clever, bringing that with you,” he said, “though we’re in some trouble should we decide to leave the circle.”

“What happens then?”

“Then,” said Mr. Morrison, “then we shall resort to other means.”

The wolf moved closer to them, and Sophie gripped Lucy’s arm. Mr. Morrison, for his part, remained motionless and apparently unperturbed.

“You are most calm, sir,” said Lucy.

“I have taken you at your word that it is monkshood,” he said. “You are certain it is?”

“My father taught me to recognize and distinguish plants,” she answered.

“Then it is monkshood,” said Mr. Morrison.

The wolf walked slowly, casually, around the furnishings, and approached the circle with a cautious snort. It stopped and sniffed again at the thin line of monkshood and let out a whimper, taking a few steps back. When it was perhaps twenty feet distant, it stopped and turned toward the door, but it did not move. Instead it watched something else with great interest, and it took Lucy a moment to see that there was a light approaching, moving raggedly as whoever came ascended the stairs. Then a figure appeared in the doorway holding a candle in one hand. It let out a whistle, and the wolf ran to it.

“Ah, well done, boy,” Byron said to the wolf, patting it upon the head with his free hand. “You have caught the intruders.”

Byron’s delighted grin reflected the two lights. He wore a dressing gown, open to the waist, revealing his muscular chest. Lucy noted the gown was unusually long, trailing to the ground so as to conceal his clubfoot.

Sophie began to breathe heavily, and she pulled away from Lucy. The wolf, seeing this, turned and growled at her. Lucy grabbed the girl to keep her from leaving the circle, though she pulled wildly and began to let out low animal noises.

“What have you done with your books?” Mr. Morrison demanded.

“I do make Newstead available from time to time that the commoners might view it, but I assure you that this is not a convenient hour. And Miss Derrick, I am surprised to see you here in such company. Last time we spoke, you made it clear you did not wish to see your name compromised. I cannot think late-night excursions with such a man to be wise.”

“Byron, don’t poison this lady with the sounds of your voice,” responded Mr. Morrison coldly. “Tell me, where are the books?”

Even in the poor light, Lucy saw Byron’s face darken and his expression contort into pure rage. He jabbed a finger toward Mr. Morrison as though he thrust a sword. “You don’t demand anything of me!” he shouted, sounding very much like a madman. “This is my home. Mine! You are an intruder. Thank me for not shooting you dead, Morrison.”

In her surprise and fear, her grip slackened, and Sophie broke away, running toward Byron. The wolf turned and leapt at her. Lucy wanted to look away, but she forced herself to look and saw Sophie unclench her hand and toss a handful of something at the wolf. It must have been monkshood, because it was as though the wolf struck something in mid leap. It yelped and fell to the ground, where it began licking its haunches. The girl, meanwhile, had hurled herself at Byron and clung to him. He put his arm around her and patted her affectionately, like a man with his child. There was something else there too, Lucy thought. His movements were slow and sensual and knowing, and Lucy understood that Byron had already taken full advantage of this girl’s devotion to him.

“Lord Byron,” said Lucy, somehow emboldened by his outrageous behavior with Sophie. His defiance of all morality made her trespassing seem insignificant. “We should never have come here without your leave if we thought you were home, but we believed you in London, and the matter too important to wait. Please, you must tell us. Where are the books?”

“Oh, Lucy. If you had come to me, I could deny you nothing. You know what is in my heart. But I cannot abide your aiding this man.”

“Your heart?” Mr. Morrison demanded. Now he retrieved from his pocket a pistol, which he pointed at Byron. “What feelings do you pretend to have for this

lady?”

This, clearly, was the “other means” to which he had alluded. “Please,” Lucy said to Byron. “I know not what is between you and Mr. Morrison, but you must understand this is a matter of the utmost importance to me. It is for my sake that we have come here. I beg you send away the wolf and tell us what we want to know.”

Byron appeared to soften at this. He said something to the wolf that Lucy did not understand, but apparently it did. It rose upon its legs and trotted out of the room.

With his arm still around Sophie’s shoulders, Byron faced Lucy and Mr. Morrison. “My means are not what I would wish. Consequently, I sold my library.”

“To whom?” demanded Mr. Morrison.

Byron grinned at him. “I shan’t tell you. Now, what shall you do about it?”

Mr. Morrison snorted. “You think we won’t be able to find out?”

“I suppose we shall see.”

Sophie refused to go with them. When Lucy approached the girl, she simply clung tighter to Byron and turned away.

“This is unworthy of you,” she told him.

He smiled at her. “This is who I am, Lucy. I live by my own law, not the world’s, but I like to believe my code is not without honor. I do not harm or deceive her. She wishes to be with me upon such times I find agreeable, and I cannot tell her that she ought not to wish it.”

“She loves you,” said Lucy. “What will her life be when you walk away with hardly a recollection of her?”

“She knows I will not remain,” he said, “and she chooses to stay.”

They turned to go and Sophie ran over to Lucy, giving her a warm hug. When they broke off, she scribbled something on her slate. Thank you. I will be well.

“I hope so,” Lucy said.

Sophie took her chalk once more, her hand moving quickly over the slate. She held it out, this time at such an angle that, even at a distance, Mr. Morrison would be unable to see. It read, Books sold to Hariet Dier, Kent.

Lucy struggled to keep her face from showing her surprise. She knew at that instant that she would not tell Mr. Morrison. He wanted those pages for his order. He wanted to stop the Luddites. Lucy was still uncertain about the Luddites themselves, and how wholeheartedly she endorsed their cause, but she knew that even if Mr. Morrison wanted to help her, once his order took hold of the Mutus Liber she would never have another chance to take the pages herself.

She hugged Sophie again, wished her well, and departed with Mr. Morrison, adopting his mood of disgust and defeat.

Outside Newstead, Lucy walked with Mr. Morrison, neither of them speaking for some time. At last he said, “I don’t recall you mentioned that you knew Byron.”

“Nor did you,” she answered. “You and he appear to loathe each other.”

“And you and he appear to have feelings of another sort.”

Lucy felt herself stiffen with anger. “How dare you presume to judge me, sir! After what you did to me. And—and I was only sixteen, and you—” She turned away, shaking, feeling tears burning upon her face, and not wanting him to see.

She did not hear him walk toward her, but when he spoke, she sensed he stood directly behind her. “I am sorry, Lucy.”

“You are sorry,” she said, not troubling to turn to him. “You have the luxury of apologizing and forgetting, but I have not. I am reminded of it nearly every day of my life.”

It occurred to Lucy she was being unfair. Mr. Morrison might well have been more sensitive had she not cast a love spell upon him. It might not be his fault entirely that he was so callous about what he had done to her in the past. More important, the spell might well be broken if she distressed him too much, so she attempted to calm herself. She wiped her eyes with her hands and turned to him.

“I aided him once,” she said, trying, not entirely successfully, to keep her voice from trembling. “Using the cunning craft. It made an impression upon him, and he chose to express his feelings by making me a very improper offer. I hope I need not add that I rejected it as the insult it was. That is the extent of my history with him. What is between you?”

Mr. Morrison appeared to mull over what he had just heard. Then he sniffed. “You have met him. You have seen how he behaves, how he treats women—even those too unfortunate to know their own interest. I cannot abide such a man, and circumstances have thrown us together enough times for our opposing natures to clash.”

“What is your next step?” asked Lucy, making every effort to lighten her voice. She wished him to believe her anger had passed.

“I cannot yet say. I will report to my order and we will formulate a plan.”

Lucy let out a sigh as they approached his horse. “At least we did not need the amethyst, for we encountered no ghosts.”

Mr. Morrison let out a laugh. “Miss Derrick, the amethyst is the only reason we did not.”

23

THE FOLLOWING MORNING WORD ARRIVED FROM NORAH GILLEY that they were going to London two days thence, and Lucy began to make preparations to leave her uncle’s house. While she packed her things, a boy arrived at the house with a note from Mr. Morrison, who begged she meet him once again at the chocolate house. When she arrived, he was loitering outside and looking agitated and demonstrating no particular interest in chocolate.

“I must leave Nottingham at once,” he told her, moved nearly to tears by what he said. He took both her hands and looked directly into her eyes. “I ought to have gone already, but I could not leave without seeing you.”

“I go to London in two days, with Miss Gilley. Where do you go?”

“I have sworn an oath of secrecy. I can tell you only that I leave England.”

Lucy took a moment to consider this news. If there were parts of the book outside England, she could never retrieve them herself. Maybe it was best not to ask too many questions. Better he should go, find the pages, and then hopefully she could persuade him to give them to her. She hated to let him leave with the love magic still upon him, but for the sake of her niece, Lucy had no choice.

“Perhaps,” she said, “when you have completed your quest, you will find me in London.”

He let go of her hands and began to pace in short strides. “If there is a way to do so without compromising the safety of this nation, then I will find you, Lucy. As soon as I can.”

After saying this, he proceeded to make many declarations. He spoke of how they would be together once this dark hour had passed. If he noted that she did not encourage, or even respond to, these speeches, he made no sign of it. At last, greatly moved by his own sorrow, he departed, and Lucy wondered if she would ever see him again. If she wanted the missing pages of the book, she supposed she would have to.

Shortly before she left for London, Mr. Olson came to call. She longed to say that she was unwell and to send him away, but he had suffered much, and even if he had also caused suffering, Lucy did not wish to be cruel. More than that, he had loved her after his own fashion, and she must not hate him for that. On the other hand, he had never declared he no longer wished to marry her, and she did not want to hear him press his case. However, Lucy knew she would likely have to face many things, many people, she would rather avoid. Best to get into the habit.

She went downstairs and found him in the parlor, sitting with his legs pressed close together, hands in his lap, looking uncomfortable, and yet, for all that, he appeared, if not precisely happy then at least contented. His eyes were wide and bright and attentive, his suit new and neat and clean. He had cut his hair into the fashion of late, and it was neatly combed. As she entered the room, he rose to his feet and bowed at her, and he had the air of a man who believed in his own significance.

“Miss Derrick,” he said when they were seated, “I understand you are to leave for London for the remainder of the season.”

“Perhaps not so long. Perhaps longer,” she said. “I do not yet know.”

He nodded. “I thought it would be wrong not to take my leave of you. I know that matters did not end between us as I had w

ished, and I spoke some words which I now regret. Nevertheless, I hope when you think of me, you will think well.”

Apparently Mr. Olson had set aside any intention of pursuing the wedding, and he’d simply neglected to mention that fact to the bride. In any case, this was good news, making her inclined toward generosity. “With all my heart. I have never said how sorry I was to hear of your mill, and the reversals you suffered. I do not love such enterprises for their consequences to the men of Nottingham, but I never wished that you should face these difficulties.”

“On that score you need have no fear,” said Olson. “My machines were destroyed and I had no money to replace them, but opportunities have arisen, and I now construct a new mill in a new location. From this adversity, great things have arisen.”

He forced a smile at her. Perhaps he wished to show her what she had neglected to seize, but Lucy did not think so. She believed he was just as relieved to have escaped her as she was to have escaped him.

“I wish you much prosperity.”

“I cannot see how we can fail,” said Mr. Olson. “Lady Harriett, my patroness, has a good head for such matters as these—a remarkable trait in a woman.”

Lucy stood up and wrung her hands, and seeing that he stared at her she sat back down again. She opened her mouth, to say that he must not take her money, must not do business with her, but knew how it would sound, and she had no means of convincing him. Nothing she could say would be creditable, and so she put her hands in her lap and looked away. “I can only wish your business brings you the success you desire.”

“Thank you, Miss Derrick,” he said, seeming to find nothing odd in her behavior. “I am sanguine it will all be well. You see now, you would not have suffered for being married to me.”

“And yet,” she offered. “I sense that your feelings have altered.”

He nodded. “It is the strangest thing. You must understand that I know you are a pretty girl, but I have never valued such things in a wife. I have never wanted to marry for anything but property. It merely happened one day that I thought I was in love with you, and then one day I thought I was not. I suppose love is strange in that way.”

The Whiskey Rebels

The Whiskey Rebels Renegades

Renegades The Twelfth Enchantment: A Novel

The Twelfth Enchantment: A Novel The Day of Atonement

The Day of Atonement The Devil's Company

The Devil's Company Randoms

Randoms Paleo / The Doomsday Prepper

Paleo / The Doomsday Prepper Rebels

Rebels A Spectacle of Corruption

A Spectacle of Corruption The Twelfth Enchantment

The Twelfth Enchantment The Coffee Trader

The Coffee Trader The Ethical Assassin

The Ethical Assassin The Devil’s Company: A Novel

The Devil’s Company: A Novel The Double Dealer

The Double Dealer The Whiskey Rebel

The Whiskey Rebel A Conspiracy of Paper bw-1

A Conspiracy of Paper bw-1 The Devil's Company bw-3

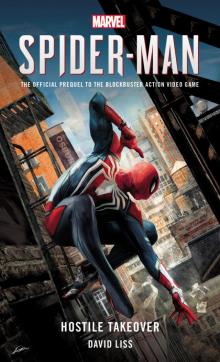

The Devil's Company bw-3 Marvel's SPIDER-MAN

Marvel's SPIDER-MAN