- Home

- David Liss

The Devil's Company Page 22

The Devil's Company Read online

Page 22

I did not love to do it, but I saw the sense of his plan, and I understood Carmichael had proposed it not out of an altruistic impulse but because it was the soundest course. So I allowed him to lead me toward the window he had in mind. It was stuck with disuse, but I managed to pry it open and have a look out. The stones were, indeed, quite rough. A man afraid of heights or unused to handling himself in awkward situations—such as the uninvited entry or exit from premises not his own—might have trembled at this sight, but I could only think that, in the past, I’d managed far worse and in rain and snow too.

“I’ll leave the window open just enough to give you something to grip when you return,” he said. “But I’ll have to lock the door behind me, so those picks of yours had better be good.”

It was not the picks that would be tested but the picker, but I had my share of experience, so I merely nodded. “You are certain you wish to remain?”

“’Tis the best course. Now off with ye.”

So I was off, out the window. Balancing on the thankfully ample ledge in the darkness of night, I caught hold of a jutting rock and forced myself up to a ledgelike protrusion, and then another, and then, with an ease I found almost troubling, I was on the roof. There I pressed myself flat where I might have a good view of the door. I could hear from the building a muffled commotion, but no more than that. And then nothing but the sounds of London at night: the distant cries of street vendors, the squawks of eager or outraged whores, the clatter of hooves on stone. Across the courtyard I heard the coughing and cackling and grumbling of the watchmen.

A light rain soaked my greatcoat and clothing through to my skin, but still I remained until I saw a group of men depart from the warehouse. From my lofty position I could not hear their words or determine who they were, except that there were four of them and one, from the size of the bulk under his coat, I believed must be Aadil. Another must have hurt himself on the stairs, I thought, because one of his fellows helped him along.

I continued to wait for some hours until I feared that light would soon destroy my cover, and so, with much greater difficulty and trepidation than on my ascent, I carefully made my way back down the ledge of the wall to the window sill and pried open the window—already ajar as Carmichael had promised. I then found that my picks were unnecessary, for the door had been left closed but unlocked. I knew not if my ally had done this by mistake, as an aid to me, or if the men come to inspect the premises had been careless. At the time I hardly cared. I should have cared, I later realized, but at the time I did not.

Now, without benefit of a candle, I made my careful way down the stairs, wondering all the while if Carmichael would rejoin me or if he had somehow managed to slip out without my noticing. There was no sign of him, however, and once on the ground floor, I studied the premises through a window until I felt certain I could leave undetected. It was then a matter of another half an hour of snaking through shadows to avoid the watchmen and make my departure. I arrived home in time to sleep an hour before rising once more to greet the day and the terrible news it would bring.

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

ECAUSE I WAS TIRED AND SULLEN FROM MY DIFFICULT AND ultimately unproductive night, I did not notice the dour mood when I arrived at the warehouses in the East India yard—at least not at first. It took me a few minutes to see that the watchmen and warehouse workers all were equally sullen and gloomy.

“What’s happening?” I asked one of them.

“There’s been an accident,” he told me. “In the early morning. No one knows what he was doing there; he had no business. Aadil thinks he was stealing, but Carmichael was in the west warehouse—where all the teas are kept, you know. And there was an accident.”

“Was he hurt?” I demanded.

“Aye,” the fellow told me. “He was hurt unto death. Crushed like a rat under the teas he was aiming to steal.”

TEAS.

A clever enough cover, I supposed, since whatever Forester and Aadil were up to, it had nothing to do with teas. And as there could be no defensible reason why Carmichael would have been moving crates in a tea warehouse in the small hours of the night, the only available conclusion was that he had been guilty of that most common of crimes, pilfering from the warehouses to augment his meager income.

These transgressions were an open secret and were allowed so long as no one grew too greedy. Indeed, the watchmen and warehouse workers were paid poorly because it was understood that they would augment their income with a judicious amount of socking. If their remuneration was increased, the logic went, they would sock no less, so there could hardly be anything to gain by paying them a living wage.

I remained stunned for long moments, standing still while men rushed about me. I broke out of my malaise when I saw Aadil pass by: I reached out and grabbed his sleeve.

“Tell me what happened,” I said.

He met my gaze and let out a laugh. How ugly his already unpleasant face grew when he wore a mask of cruel mirth! “Maybe you tell me. You overseer of watch.”

“Pray, don’t be petty. Tell me.”

He shrugged. “Why Carmichael here last night, I wonder? He where he not supposed to be. He doing what he not supposed to do, taking tea for himself. Maybe in hurry, afraid he get caught. Take chances. Get crushed.” He shrugged again. “Better than be hanged, yes?”

“Let me see the body.”

He looked at me quizzically. “Why for you want see it?”

“Because I do. Tell me where they’ve taken it.”

“Already carried away,” he said. “I know nothing where. Coroner, maybe. Family? No one tell me. I no ask.”

It was only with the greatest restraint that I was able to have this conversation. I had no doubt that Aadil had killed Carmichael, with Forester’s implicit or explicit approbation. Yet these were suspicions, conjectures I could not prove, and in the end they mattered little. All I knew was that Carmichael had acted for me and had died for his trouble, and I was powerless to see justice served on his behalf.

Lest I betray my emotions or reveal that I knew more of the matter, I walked away, heading for the interior of Craven House.

Did Aadil suspect my involvement? He kept secrets from me, but that was to be expected. Still, Carmichael had violated the sanctum of the secret warehouse only after I had come to work there. Forester knew I was working for Ellershaw and he mistrusted Ellershaw. Why did they not come after me? There was certainly no good reason to believe they would not, simply because they had not yet done so.

It was now more urgent than ever that I find out what Forester was keeping in that warehouse or, since we had discovered the banality of the room’s contents, why he was keeping it. Thus, with no useful outlet for my rage, I pursued the matter the only way I could imagine doing so—I went to speak to the accounts keeper, Mr. Blackburn.

He was in his office, scratching away at a piece of paper, hunched over it as his ink-stained hand whipped pen along page. He looked up after a moment. “Ah, Weaver. I presume you are come to inquire as to the means of replacing your lost worker.”

I shut the door behind me. “I had nothing so mercenary in mind. Carmichael was my friend, and I am not so eager to see his place filled.”

He looked at me with his puzzled expression, the one he always wore when not busy with his documents. It seemed to me that he could not imagine anything as uncomfortable or messy as friendship.

“Yes, well,” he managed, after a moment, “even so, schedules have to be ordered, hmm? The yards must be watched. It would be a foolish thing to let sentiment interfere with what must be done.”

“I suppose it would,” I said, taking a seat without being invited to do so.

It was clear to me, painfully clear, that Blackburn wanted nothing so much as for me to leave, that he might go back to whatever banal task absorbed him, but I would not have it. Indeed, his discomfort might only serve to make him speak in a less circumspect manner than was, perhaps, his wont.

“May I speak

to you in confidence?” I inquired. “It is of a delicate matter, and one that involves a particularly unorthodox use of Company grounds and Company resources.”

“Of course, of course,” he said. He had set down his pen and was absently blotting the page while he looked at me. I had as near his full attention as I could reasonably expect.

“I hope I might have your confidence, sir. I should hate if my interest in righting something sloppy should be visited upon me with something so unfair as losing my post. You understand, sir, I trust. I want to do the right thing and make sure there is nothing amiss in the warehouses. Still, when there are powerful men involved, it is not always easy to be sure the right thing is in one’s best interest.”

He leaned forward, stretching his narrow frame across the desk like a turtle stretching its neck out of its shell. “You need not worry on that score, Mr. Weaver, not at all. You may speak in the strictest confidence, and you have my word that I shall not speak of what you say to anyone, not without your leave. I trust that is sufficient.”

It almost was. “I should very much like it to be,” I said, with some uncertainty. “Still, there is a great risk to me. Perhaps it would be wise if I came back when I knew more. Yes, that would be better.” I began to rise.

“No!” The word was not an order but a plea. “If you know something, we must resolve it. I cannot endure that there should be something amiss, some wound left untended, rotting upon the body of the Company. You do right, sir, in wanting to address it. I promise you, I shall do nothing you do not wish me to do. Only you must tell me what it is you know.”

It was so very odd, I thought. Here this clerk doted upon the Company as though it were a favored lapdog, or even a lover or a child. Had I not told him, he would have been driven mad by the unreachable itch, and yet he had nothing personal to gain from the intelligence, nothing personal to gain from correcting whatever impropriety to which I might allude. He was merely a man who liked to see geegaws aligned, be they his geegaws or a stranger’s, and would stop at nothing to correct an aberration.

I cleared my throat, wishing to speak in a roundabout way so that I might make his torture all the more exquisite. “Last week, Carmichael spoke to me of an impropriety. I thought the matter of little urgency and would have pursued it at a more leisurely pace, but—as you can see—I am no longer free to pursue it with him at all. And while he considered the matter of little moment, I—well, I think you understand, Mr. Blackburn. I believe we are in that way alike. I do not wish this thing to go unattended forever.”

I continued to avoid the topic, not only to further torment Blackburn but also because I wished to make it clear that I did not regard this issue too seriously. I in no way wanted to imply what I truly believed, that Carmichael had been killed over whatever I was about to say.

Indeed, he followed quite well. “Of course, of course,” he said, waving his hand at me as I spoke to further my speed of revelation.

It was time to get to the meat of it. “Carmichael mentioned to me that there was a portion of one of the warehouses, I cannot recall which one”—again, this seemed to me the best course—“in which calicoes were being secreted away by one of the members of the Court of Committees. He said these crates arrived in the dark of night, and great care was taken to be certain no one knew about them: that they were there, what they contained, or in what quantity. Now, I am not one to question members of the Court, but as overseer of the watch, the practice of regularly superseding our scrutiny struck me as troubling.”

It struck Blackburn as troubling as well. He leaned toward me, and his hands twittered in agitation. “Troubling? Troubling indeed, sir, most troubling. Secret stores, hidden quantities and qualities? That cannot be. That must not be. These records have three purposes. Three, sir.” He held up three fingers. “The establishment of order, the maintenance of order, and the securing of future order. If some men think they are above documenting their actions, if they may take and add at their own whims, then what is this”—he gestured to the vast stores of papers about the room—“what is all this for?”

“I had not thought of it from that perspective,” I said.

“But you must, you must. I do this work so that at any time any member of the Court may come here and know all there is to know about the Company. If someone chooses to run wild, sir, there is no point to it. No point to it at all.”

“I believe I understand you.”

“I pray you do. I pray it most earnestly, sir. You must tell me more of this. Did Carmichael say anything to you of which member of the Court might be acting so recklessly?”

“No, nothing of that. I don’t believe he knew himself.”

“And you don’t know which warehouse.”

Here I decided I would be wise to retrench. After all, I had to give the man something on which to base his inquiry. “I believe he might have mentioned a building called the Greene House, though I cannot be certain.”

“Ah, yes. Of course. Bought from a Mr. Greene in 1689, I believe, a gentleman whose loyalties and preferments were too closely bound with the late Catholic king, and when he fled, Mr. Greene did not long linger. The Greene House has generally been used as a storage facility of, at best, tertiary importance. Indeed, it is scheduled to be brought down and replaced in future. If a devious man wished to hide something within the yard, that might well be the place to do it.”

“Perhaps you can find some records,” I suggested. “Manifests and such like. Something that will let us know who is misusing the system and for what purpose.”

“Yes, yes. That is the very thing. It is the very thing to do. This sort of irregularity must not be countenanced, sir. I shan’t turn a blind eye, I promise you.”

“Good, good. I am glad to hear it. I trust you will let me know if you discover something.”

“Come back later today,” he mumbled, already opening a massive folio that spewed out a storm of papers. “I shall have this problem solved, I warrant.”

IN CRAVEN HOUSE ITSELF, the mood was black among the servants. Carmichael had been well liked, and his death darkened everyone’s spirits. I was passing through the kitchens to attend to my duties on the ground when Celia Glade stopped me by placing her slender fingers around my wrist.

“It’s very sad news,” she said quietly, not bothering to affect her servant’s voice.

“Indeed it is.”

She released my wrist now in favor of my hand. I confess I had a difficult time not pulling her close. The sight of those great eyes, her shining face, her scent. I felt my body rebelling against my intellect, and despite the cruel violence of the day I longed to kiss her. Indeed, I believe I might have done something as dangerous as that had not a pair of kitchen boys entered at that moment.

Celia and I parted wordlessly.

LATER THAT AFTERNOON, after a black day of grumbling among the men and of my having to resist the impulse to strike Aadil in the head each time his back was turned, I returned to Blackburn’s office, hoping to find some useful intelligence. Alas, it was not so.

His face was pale and his hands trembling. “I can find nothing, sir. No records and no manifests. I shall have to order an inventory of the Greene House, discover what is there, and attempt to determine how it came and where it is destined to go.”

“And by whom,” I proposed.

He looked at me with a knowing expression. “Just so.”

“Except,” I countered, “do you really wish to pursue a general investigation? After all, if a member of the Court has gone to such lengths to hide his scheme, he may go one step further.”

“You mean remove me from my place?”

“Tis something to ponder.”

“My services have never been questioned.” A tone of desperation now entered his voice. “I have been here for six years, sir, working my way into this position, and no one has spoken anything but words of praise. Indeed, more than one member of the Court has wondered aloud to me how the Company functioned before my

arrival.”

“I doubt none of that,” I told him. “But I hardly need tell you, sir, that a man of your position is at the mercy of those who stand above him. One or two unjust persons of power could undermine all you have done in the time you have toiled here. You must know it.”

“Then how do we proceed?”

“Quietly, sir. Very quietly. It is all that can be done for the nonce, I’m afraid. We must both be determined to keep our eyes open, looking for any signs of deception, and perhaps then we will be able to link this aberration to its origins.”

He gave a sullen nod. “Perhaps you are right. I will certainly do all I can to discover more, though I shall follow your advice and pursue the matter quietly, with books and ledgers rather than with words.”

I commended him for his determination and left his office; indeed, I was out of Craven House and nearly at the main warehouse when I stopped in my tracks.

The idea came upon me all at once and in such a rush that I nearly ran back to Blackburn’s office, though doing so was hardly necessary. He would be there, and time was certainly of no great issue. It was for myself that I ran, for I desired above all else to know at once.

I entered once more and, as was now becoming my habit, I closed the door. I sat down before Mr. Blackburn and offered him a generous smile. The impulse to bombard him with questions was strong, but I beat it back. To demand he tell me what I wanted to know might strike him as, in its own way, disorderly. I knew he did not like to speak of rough edges and puzzle pieces that did not fit, and I would have to approach the question with a certain amount of caution.

“Sir,” I began, “I was halfway across the yard when I had a sudden desire to return and tell you that I have come to be a great admirer of yours.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“Your gift for order, sir, and regularity. It is the very thing. You have inspired me in my work with the watchmen.”

“I am flattered by your words.”

“I say no more than what any man must acknowledge. I wonder, however, if there is more to know than what I have gleaned from our brief conversations.”

The Whiskey Rebels

The Whiskey Rebels Renegades

Renegades The Twelfth Enchantment: A Novel

The Twelfth Enchantment: A Novel The Day of Atonement

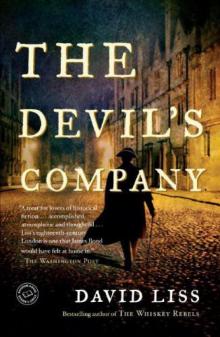

The Day of Atonement The Devil's Company

The Devil's Company Randoms

Randoms Paleo / The Doomsday Prepper

Paleo / The Doomsday Prepper Rebels

Rebels A Spectacle of Corruption

A Spectacle of Corruption The Twelfth Enchantment

The Twelfth Enchantment The Coffee Trader

The Coffee Trader The Ethical Assassin

The Ethical Assassin The Devil’s Company: A Novel

The Devil’s Company: A Novel The Double Dealer

The Double Dealer The Whiskey Rebel

The Whiskey Rebel A Conspiracy of Paper bw-1

A Conspiracy of Paper bw-1 The Devil's Company bw-3

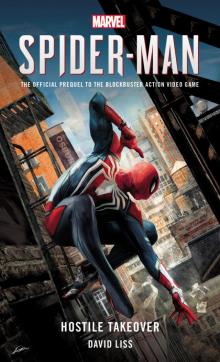

The Devil's Company bw-3 Marvel's SPIDER-MAN

Marvel's SPIDER-MAN